There’s something powerful happening in communities across the world. People are rediscovering their connection to the landscapes they inhabit. This movement, known as bioregional community development, represents a fundamental shift in how we think about belonging. Rather than identifying primarily with political boundaries or economic zones, bioregional communities anchor their identity in the living systems that surround them.

Rediscovering Place-Based Identity

For most of human history, communities were intimately tied to their local ecosystems. People knew which plants grew when, where water flowed, and how weather patterns changed throughout the year. This wasn’t just practical knowledge—it formed the foundation of cultural identity.

Industrialization and globalization gradually severed these connections. Food now travels thousands of miles before reaching our plates. Water arrives through invisible infrastructure. Our homes maintain constant temperatures regardless of season. While these developments brought tremendous benefits, they also disconnected us from the living systems that sustain us.

Bioregional community development seeks to rebuild these connections without abandoning modern progress. It’s not about returning to an idealized past, but rather creating futures where human communities thrive as conscious, contributing members of their local ecosystems.

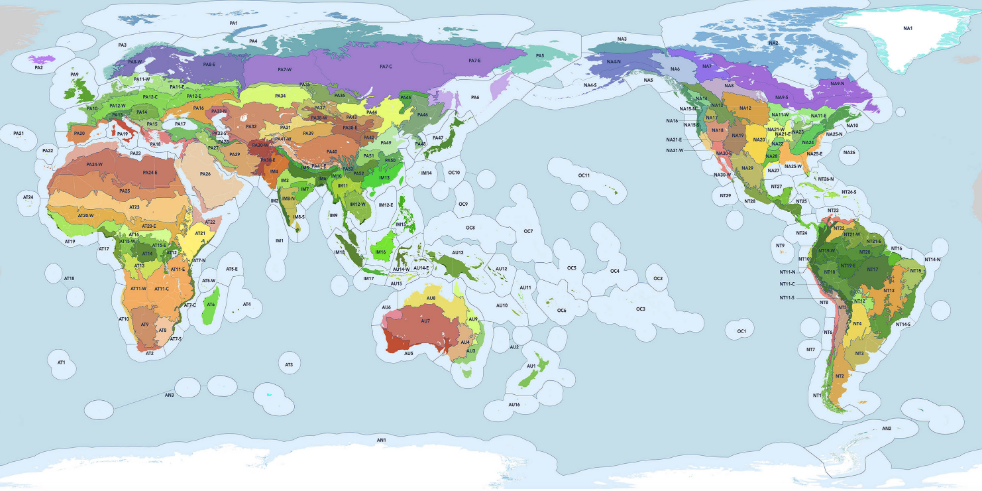

The approach begins with a simple question: what makes this place unique? Beyond government boundaries, what watersheds, mountain ranges, forest systems, or coastal areas define where we live? Understanding these natural features provides the foundation for bioregional identity.

Understanding Bioregions as Living Systems

A bioregion isn’t just geography—it’s a living system with distinctive climate patterns, watersheds, soil types, native plants, and wildlife. These elements interrelate in complex ways, creating a unique ecological character that distinguishes one region from another.

Watersheds often serve as natural bioregional boundaries. Water flowing through landscapes connects communities upstream and downstream in tangible ways. When communities identify with their watershed, they naturally develop concern for water quality and flow patterns.

Seasonal rhythms provide another foundation for bioregional identity. Which wildflowers bloom first in spring? When do migratory birds arrive? What weather patterns mark the transition between seasons? These cycles create a shared temporal experience among inhabitants of a bioregion.

Native ecosystems—whether forests, grasslands, deserts, or wetlands—harbor distinctive plant and animal communities that have evolved together over millennia. These ecological relationships create the unique character and resources of each bioregion.

Geological features like mountain ranges, river valleys, or coastal formations shape everything from local weather patterns to traditional travel routes. These enduring landscape elements often formed the basis of indigenous territories long before modern borders were drawn.

Social Dimensions of Bioregional Development

Bioregional development extends beyond ecological understanding to encompass social, economic, and cultural dimensions. Communities aligned with bioregions naturally develop distinctive foodways, building practices, celebrations, and economic activities that reflect local conditions.

Food systems offer an immediate connection to bioregions. What grows well locally? Which fishing grounds or hunting areas have traditionally supported the population? How do seasonal changes influence diet? Communities reconnecting with local food production discover both practical benefits and deeper place attachment.

Building traditions naturally evolve to suit local conditions when communities embrace bioregional thinking. Materials available locally, climate considerations, and traditional knowledge combine to create architectural approaches uniquely suited to place.

Cultural celebrations often emerge around ecological events—harvest times, salmon runs, seasonal transitions, or wildlife migrations. These shared experiences strengthen community bonds while reinforcing connection to natural cycles.

Economic activities aligned with bioregional realities prioritize industries and approaches appropriate to local ecosystems. Rather than imposing identical economic models everywhere, bioregional economies build on the particular gifts and constraints of their places.

Modern Applications and Examples

The bioregional approach has inspired diverse initiatives across the world. These examples demonstrate how communities are applying these principles in contemporary contexts.

The Cascadia movement in the Pacific Northwest transcends the US-Canada border to unite communities sharing the distinct rainforest ecosystems, salmon watersheds, and volcanic mountains of this unique bioregion. Cultural identity based on these shared natural features has inspired poetry, art, economic cooperation, and environmental protection efforts.

Watershed restoration committees throughout North America bring together diverse stakeholders who might disagree on politics but share concern for the rivers connecting their communities. These efforts have revitalized degraded ecosystems while building social capital across traditional dividing lines.

Urban bioregional initiatives recognize that cities exist within natural systems too. Programs to daylight buried streams, restore native plant communities in parks, and create wildlife corridors through urban areas help city dwellers recognize and strengthen their connection to local ecology.

Indigenous-led conservation efforts often embody bioregional principles, drawing on centuries of place-based knowledge to address contemporary challenges. These initiatives demonstrate how traditional ecological knowledge can complement scientific understanding for more effective stewardship.

Food sovereignty movements worldwide embrace bioregional thinking by rebuilding local food systems aligned with ecological realities. From urban community gardens to regional agricultural cooperatives, these efforts reconnect people with the particular growing conditions of their home places. For more resources on building food systems aligned with your bioregion, visit our bioregional planning guide.

Practical Steps Toward Bioregional Community

Communities interested in strengthening their bioregional identity can begin with simple, accessible steps that gradually build deeper connections to place.

Watershed awareness offers an excellent starting point. Which rivers, streams, or aquifers provide your water? Where does water flow after it leaves your community? Simple watershed mapping exercises help people visualize their place within larger hydrological systems.

Seasonal food calendars help community members reconnect with local ecological rhythms. Documenting when native berries ripen, when particular fish run, or when specific vegetables thrive creates practical knowledge while highlighting the unique gifts of your bioregion.

Natural history education—whether through formal programs or informal community walks—builds collective understanding of local ecosystems. Learning to identify native plants, understand wildlife behavior, and recognize ecological relationships helps residents see themselves as part of a living system.

Place-based celebrations create cultural expressions of bioregional identity. Festivals marking seasonal transitions, harvest times, or ecological events build community while strengthening connection to natural cycles.

Collaborative mapping projects help communities visualize their bioregion beyond political boundaries. Maps showing watersheds, wildlife corridors, traditional territories, and ecological features provide a shared reference point for bioregional identity.

Challenges and Considerations

Bioregional development faces significant challenges in our highly globalized, mobile society. Addressing these considerations thoughtfully helps communities build approaches that work within contemporary realities.

Administrative boundaries rarely align with ecological ones. Rivers cross international borders, mountain ranges span multiple states, and watersheds encompass numerous jurisdictions. Bioregional communities must develop creative governance approaches that work within or alongside existing political structures.

Population mobility presents another challenge. When people frequently move between places, developing deep bioregional knowledge becomes difficult. Communities can address this through robust orientation programs that help newcomers develop place connection and through technologies that make local ecological information more accessible.

Economic globalization often works against bioregional priorities. Communities developing local, ecological economies must navigate tremendous pressure from global economic forces. Gradual approaches that build resilience while remaining economically viable offer the most sustainable path forward.

Cultural diversity within bioregions presents both challenges and opportunities. Different cultural groups often have varying relationships with the same landscape. Inclusive bioregional development honors these diverse perspectives while seeking shared understanding of place.

Climate change complicates bioregional development as ecological conditions shift. Communities must balance honoring historical ecological patterns with adapting to new realities, a delicate process requiring both traditional knowledge and scientific understanding.

Future Directions for Bioregional Communities

As environmental challenges intensify and social systems evolve, bioregional approaches offer promising directions for community resilience and ecological health.

Climate adaptation strategies naturally align with bioregional thinking. Communities that understand their local ecosystems can better anticipate climate impacts and develop appropriate responses based on specific local conditions rather than generic solutions.

Inter-bioregional cooperation represents an emerging frontier. Just as ecosystems interact at their edges, bioregional communities are developing protocols for respectful exchange with neighboring regions, creating networks of place-based communities that collaborate on shared challenges.

Technology, often seen as opposed to place-based living, can actually support bioregional connection when thoughtfully applied. Digital mapping tools, citizen science platforms, and knowledge-sharing networks help communities develop and maintain sophisticated understanding of their local ecosystems.

Educational innovation increasingly incorporates place-based learning. Schools that integrate bioregional knowledge throughout their curriculum help young people develop both practical skills and identity rooted in their home landscapes.

Economic relocalization, while challenging, continues gaining momentum as communities recognize the resilience benefits of meeting more needs locally. Bioregional economic development prioritizes enterprises suited to local conditions while maintaining beneficial connections to wider economic systems.

Conclusion

Bioregional community development offers a compelling alternative to placeless globalization without rejecting the benefits of modern life. By realigning human communities with the living systems that sustain them, this approach creates possibilities for greater resilience, deeper belonging, and more appropriate stewardship.

The path toward bioregional identity begins with simple curiosity about place. What makes your location ecologically unique? Which watersheds, soil types, native species, and seasonal patterns define where you live? As communities explore these questions together, they discover not just practical knowledge but foundations for shared identity rooted in the living world.

In a time of ecological uncertainty and social fragmentation, bioregional community development offers something precious: a way of belonging that connects us simultaneously to particular places and to the universal processes of life on Earth. This dual citizenship—in both our local ecosystems and the larger living world—may prove essential for navigating the challenges of our century with wisdom and grace.